We see some parallels but also differences between today’s situation and the first oil crisis in 1974. We examine the development of real estate returns between 1970 and 1999 in the context of key macroeconomic variables:

- What macroeconomic effects did the first oil crisis have on Switzerland, the US and the UK?

- How did the CHF, GDP, interest rates, inflation, commodities and stock markets develop in the higher inflation period 1970-1999?

- How strong was the impact of the first oil price crisis on real estate investments in Switzerland and internationally?

- How did real estate investments in Switzerland and international develop between 1970 and 1999? Did they offer inflation protection?

We see some “lessons learned”.

Einschätzungen zu den Sektoren:

Büro:

Die Stimmung

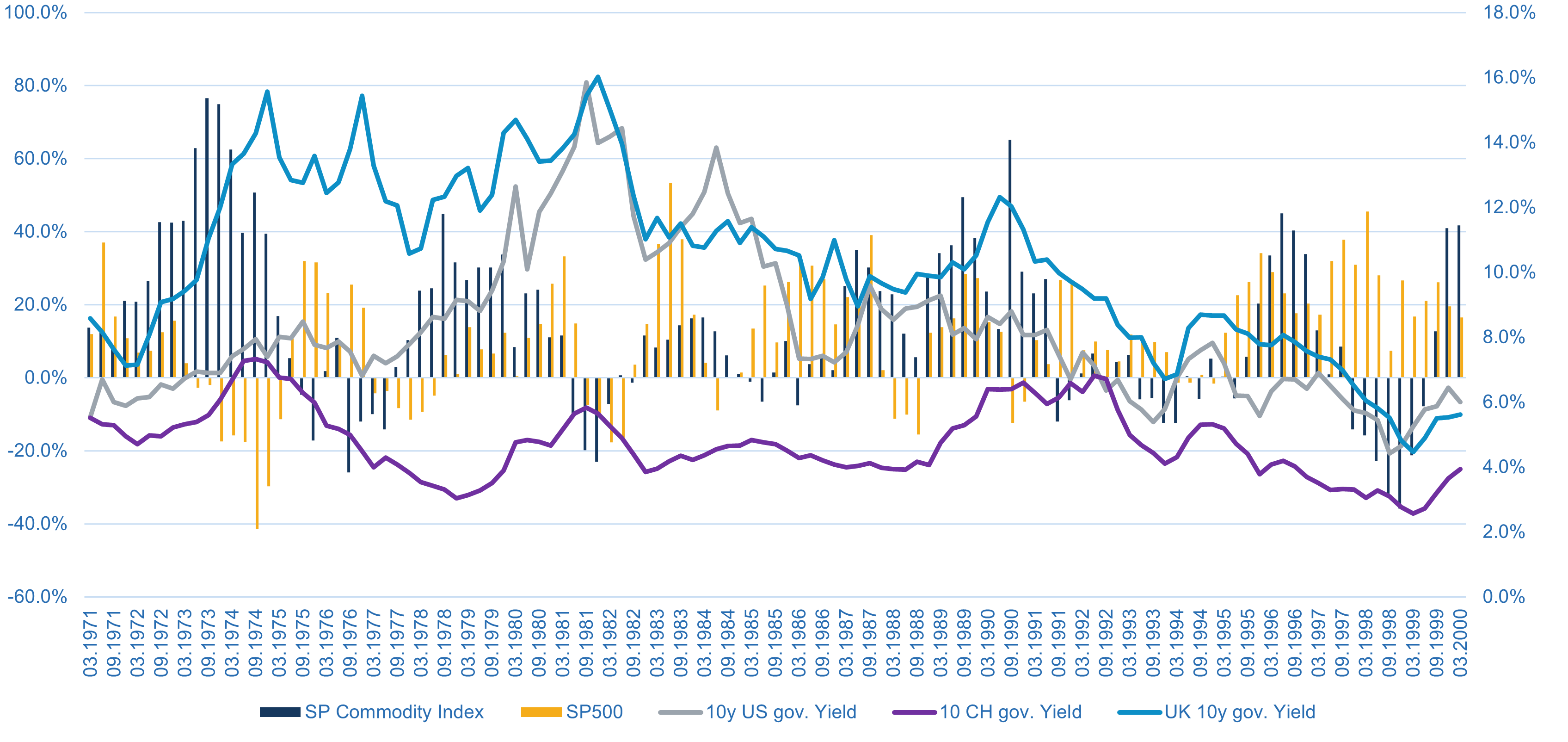

Figure 1: YoY Total Returns on Commodity and Stocks (LHS) compared with Interest (RHS)

Source: Bloomberg, FRED, Macro Real Estate

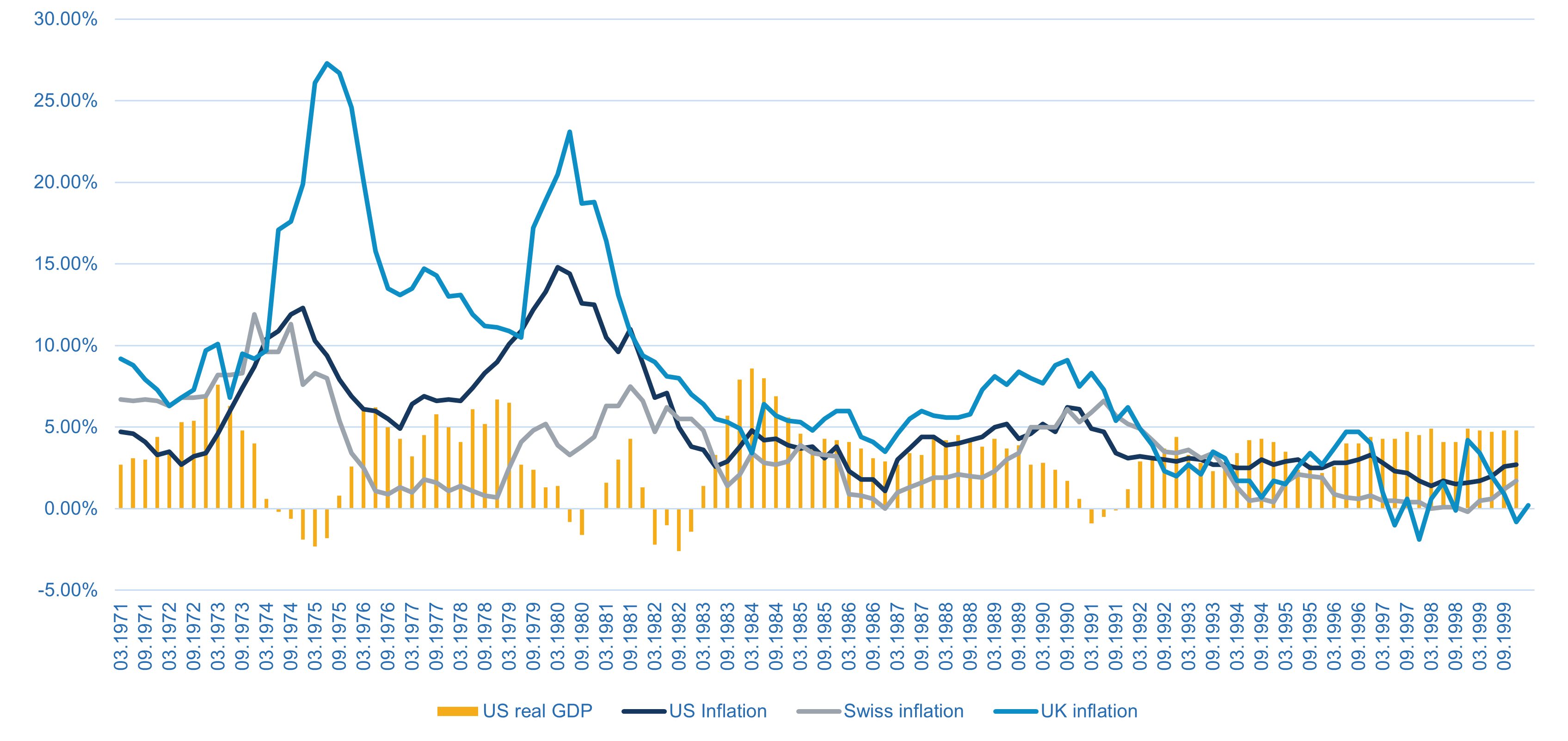

Figure 2: US real GDP growth and inflation yoy

Source: Bloomberg, FRED, Macro Real Estate

Figures 1 and 2 tell a striking story for the US, Switzerland and UK for the 1970s. The S&P GSCI Commodity Index showed a significant increase in 1973 and 1974 but reached a temporary peak towards the end of 1974. This peak was not exceeded again until the second oil crisis struck towards the end of the decade. As a result of the first oil crisis, the global economy underwent a recession (proxied here by US GDP growth rates). The SP&500 stock index unsurprisingly fell. It declined by 40% between Q3 1974 and Q4 1974. Then it recovered, but remained volatile throughout the higher phase of inflation.

Long-term interest rates in Switzerland rose by 200 basis points between mid-1973 and Q3 1974, peaking at 7.4%. We have been experiencing an almost similar movement in the last two years, albeit at significantly lower levels. Yields on Swiss government bonds are currently at 1%, while they were below -0,5% a year ago.

We can also see, that the UK experienced during the 70ies greater inflation issues compared to Switzerland and the US. This was also due to homemade structural reasons that were only addressed with the leadership of Margaret Thatcher as prime minister. Meanwhile, the UK saw inflation rates in excess of 20% and interest rates in excess of 14%.

It is also interesting that interest rates and inflation in the US were in the early 70ies at levels similar to those in Switzerland. The significant rise in interest rates in the US only came with Paul Volcker after the second oil crisis, when he raised the Fed Funds Rate to as high as 20%.

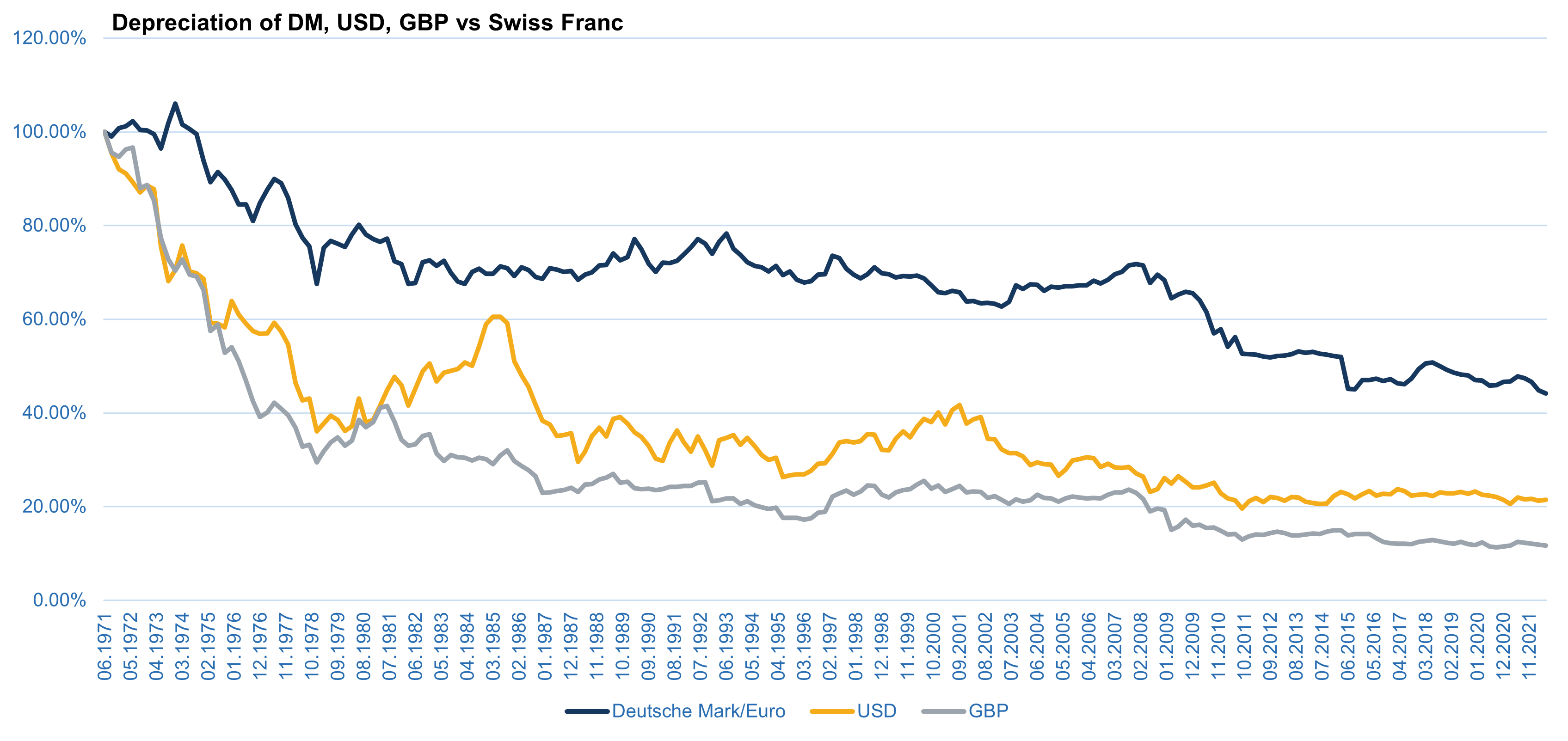

Strong appreciation of the Swiss Franc after the abandonment of “Bretton Woods”

In contrast, inflation and interest rates fell significantly in Switzerland after the first oil shock. The seemingly more benign development in interest rates and inflation in Switzerland was also the consequence of a brutal appreciation of the Swiss franc. This came with some harsh effects on the Swiss economy, especially the watchmakers industry suffered a deep crisis. As shown in Figure 3, the Swiss franc appreciated significantly during the 1970s. Against the USD and GBP, the value of the CHF even increased by 60% to 70%. This was the consequence of the collapse of Bretton Woods, that has been widely documented elsewhere.

Overall, this also meant that the interest rate for 10-year Swiss government bonds fell to almost 3% from above 7% in 1974. This corresponded to a substantially lower interest rate level than experienced before the outbreak of the first oil crisis. Swiss inflation also fell to 1% towards the end of the decade, while it had spiked to 11.9% in 1973 and remained throughout 1974 at a level around 10%.

Figure 3: Depreciation of the Deutsche Mark, USD and GBP vs CHF

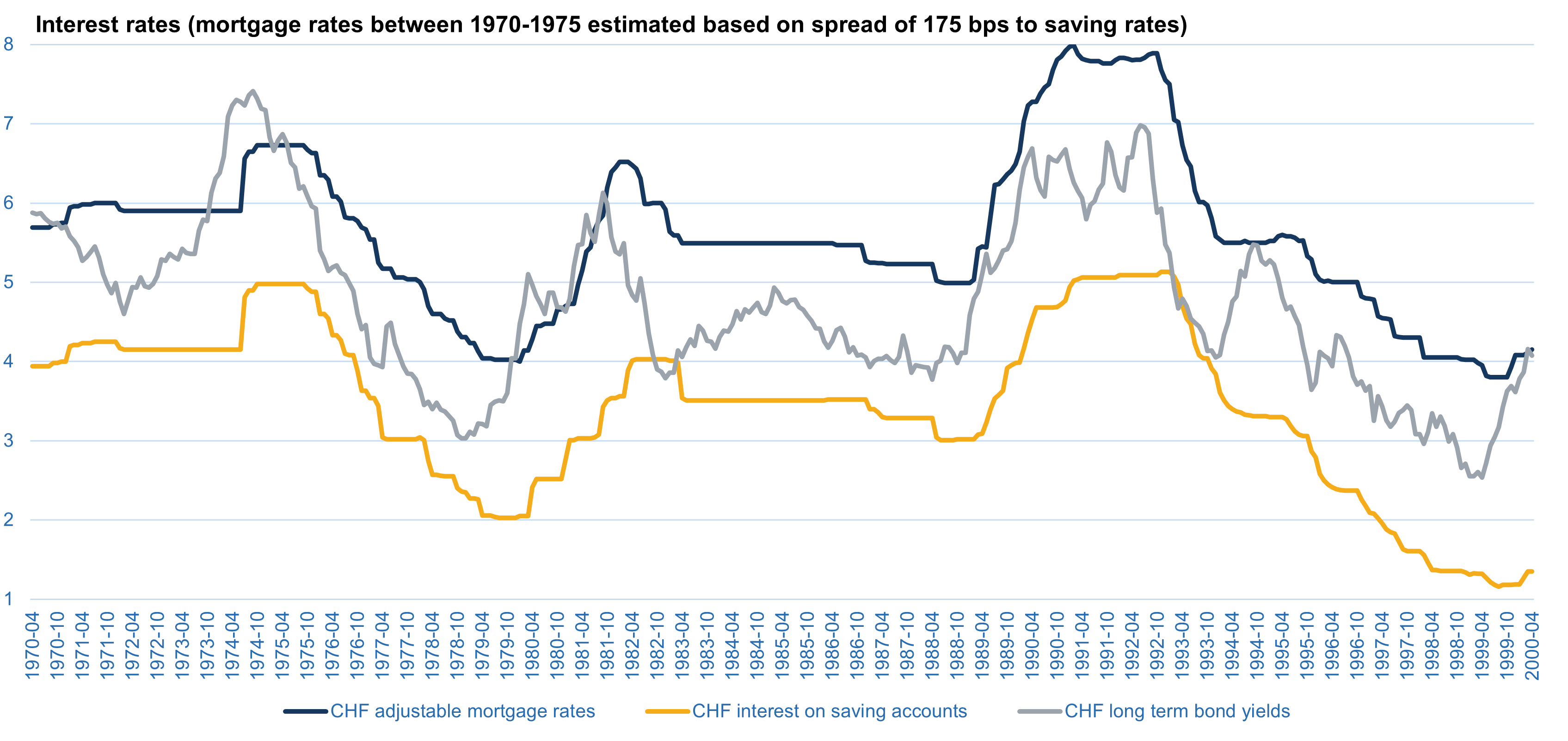

Development of Swiss mortgage interest rates 1970-2000

But what effects did this macro environment have on real estate and real estate financing markets?

In phases of shocks, the real estate financing and capital markets usually react first. That’s what we have been observing this in the current environment. Swap rates form the basis of long-term real estate financing contracts. Such interest rates have now risen significantly (about 150 basis points or even more depending on the currency and sector). This has already led to some frictions in real estate capital markets. We have learned that some commercial real estate deals in Europe have collapsed in the past few weeks. One of the reasons is the general uncertainty related to the Ukraine war, but the higher financing costs also play a role. For various listed real estate companies in Europe, financing costs are already 250-300 basis points higher than a year ago. They have risen at a higher extent than swap rates in recent weeks, as risk premiums have increased on the financial markets. The banks are now becoming more cautious and are demanding a higher margins or lend only financing at lower LTVs.

In Switzerland, long-term fixed mortgage rates for home buyers have already climbed well over 2% p.a. This practically means a doubling of the financing costs compared to the situation experienced over the last few years.

Based on these considerations, we dare to look into the past. Unfortunately, the statistics provided by the Swiss National Bank on mortgage rates only go back to 1975. Also, only variable-rate mortgage data is available, as this was the dominant way of financing then. Based on interest rate data from saving accounts, we have calculated the mortgage interest rates back to the early 1970s (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Interest on mortgages, savings deposits and 10y government bonds (all CHF)

Source: SNB, Macro Real Estate

Before the first oil crisis, we estimate the level of mortgage rates at 6% based on a spread to savings. As the rather favorable development of long-term interest rates on government bonds and inflation in Switzerland suggests, there was only a short-term, temporary shock of around 75 basis points for Swiss mortgage rates. From 1975, interest rates fell again significantly.

The historical comparison already reveals from the development of mortgage interest rates that the 1990s would be a much more difficult scenario for the Swiss real estate market, although the rise in inflation was greater in the 1970s. At the end of the 1980s, households and real estate investors not only were facing significantly higher interest rates. With an increase of over 300 basis points at the short end, the interest rate shock was three times more pronounced than in the 1970s.

Real estate investments: First oil shock leads to significant price declines

How did real estate investments in Switzerland and internationally get through the first oil crisis and how did they develop in the higher inflationary environment up to 2000? The first difficulty lies in finding meaningful data at all. Because indices for investment properties in Switzerland and abroad usually start much later.

UK is Europe’s most transparent real estate market. Even here, the IPD data only starts in 1977, the IAZI index for investment properties in Switzerland starts in 1986. Luckily, there are some academic studies that have historically reviewed real estate performance. For Switzerland I would like to thank my friend, Mihnea Constantinescu, for his great work and for supplying the indices he created. There are several studies for the UK: IPF, Robin Goodchild (then at LaSalle) and Prof. Peter Scott dealt intensively with the development of real estate performance during this period. Nevertheless, when interpreting the data, it should be noted that the data uncertainty is significantly higher than usual and the robustness of the indices is not the same as for the current periods.

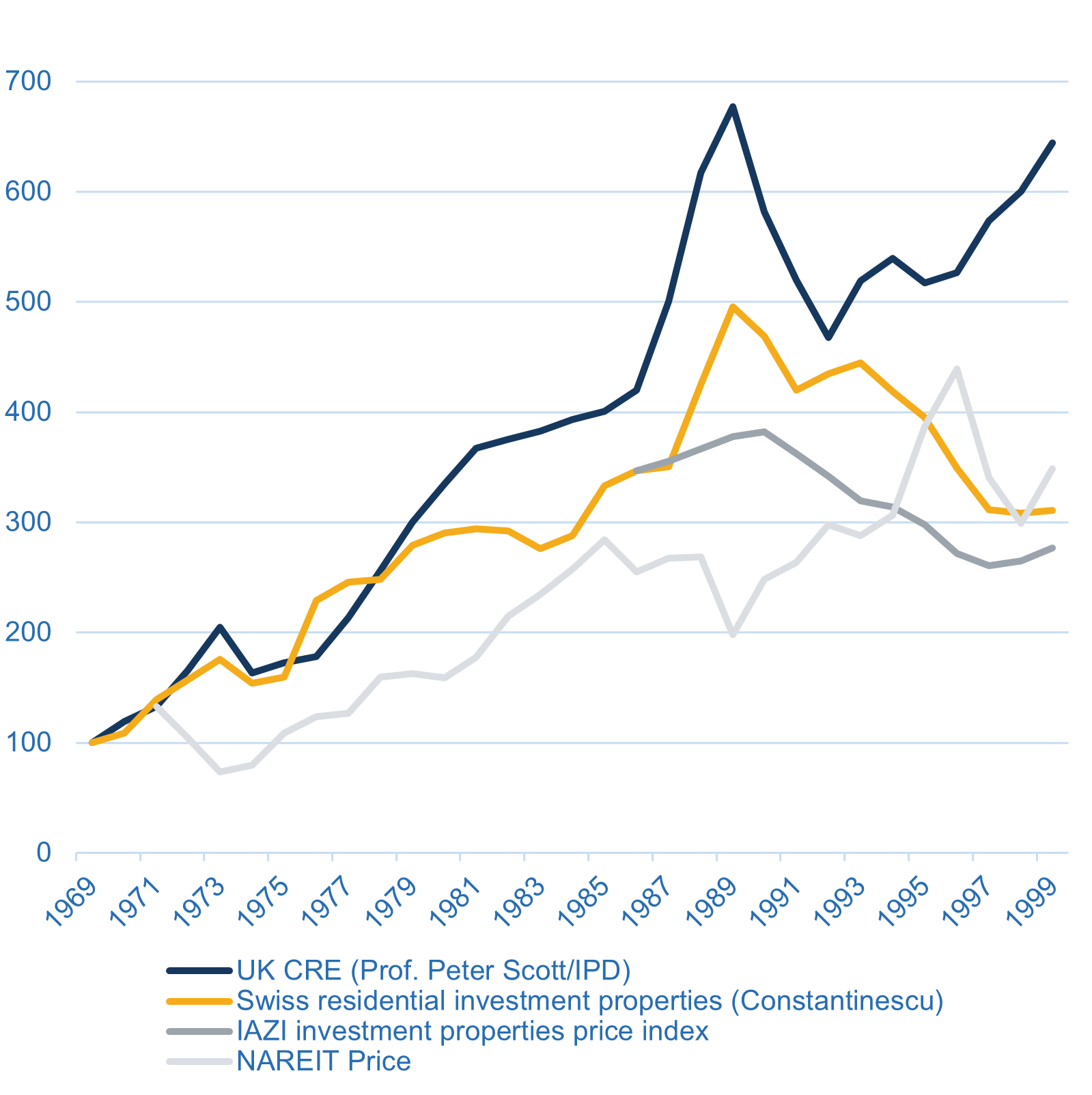

Figure 5 illustrates the nominal development of capital values between 1970 and 1999. We see international evidence that by 1974 there had been a significant correction of real estate values. In the UK commercial real estate values declined by 20% in nominal terms and around 40% in real terms. Here Prof Peter Scott described the situation in 1974 as “the great property crash”. If you are interested in the history of the real estate sector in the UK, you can read it in Prof. Peter Scott’s book: https://www.routledge.com/The-Property-Masters-A-history-of-the-British- commercial-property-sector/Scott/p/book/9781138983991

We mapped the index for Switzerland as a moving two-year average from two methods from Mihnea’s paper ( https://scholar.google.ch/citations?view_op=view_citation&hl=de&user=YF-d5CEAAAAJ&citation_for_view=YF-d5CEAAAAJ:WF5omc3nYNoC ). This shows a nominal decline in values in 1974 of 12%. In real terms it was around 20%. If we had taken the individual unsmoothed series, the decline would already be over 20% in nominal terms. We’re not sure how much noise and how much truth is behind it. That’s why we applied the first basic rule of an appraiser: When in doubt, always smooth…

The US-NAREIT index, on the other hand, is an index of listed equity REITs in the US (We had to use this because the NCREIF index for direct investments in the US only starts in 1978). The NAREIT index is clearly correlated with the general stock market performance in the short term. In the long term, however, REITs also reflect the performance of the direct market well. In contrast to the index for Switzerland and the UK, this data also includes the effect of leverage. The NAREIT Index peaked in September 1972 and fell before the first oil crisis in 1973. By its low point in December 1974, it had fallen 36% in nominal terms and around 50% in real terms. This appears high. Compared to the GFC of 2007-2009, this decline is significantly smaller. Between mid-2007 and Q1 2009, it fell a whopping 73% in nominal terms.

… but in the long term, investment properties were a good hedge against inflation

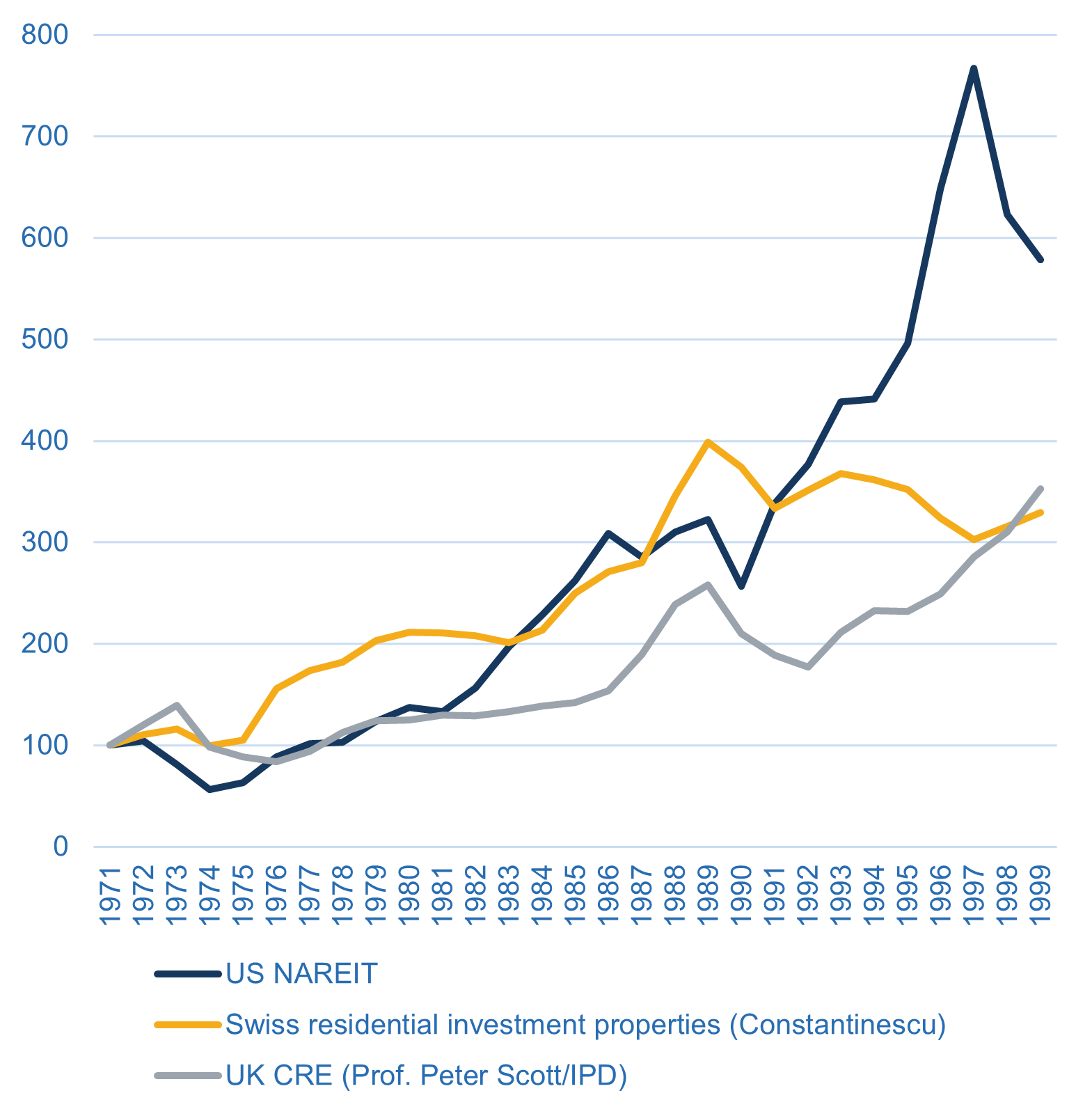

However, real estate investors are long-term investors and the question of what returns real estate investments have achieved over a longer period of time is also fundamental. The success of real estate investments depends not only on the change of capital values but also on the net income that the property can generate. Here, the income return is crucial. We have therefore calculated the total returns in Figure 6 and show them in real (inflation-adjusted) terms.

We conclude that, in particular, the high income returns on real estate during the 1970-1999 were an important factor in protecting against inflation. Property yields were between 6.8% and 7.5% in the UK and from 4.5% to 5.5% for Switzerland during 1973-1975 . They fluctuated as a result of real estate cycles, but remained between 5.5% and 9.5% for the UK and between 4.5% and 6.0% for Switzerland in the 1970s to the late 1990s. Today prime net yields are 3.5 %-4.5% in the UK and 2.0 %-2.5% in Switzerland. (For Swiss residential in the inner cities, we are currently even at 1.5% or lower)

During the 1970s, Swiss residential real estate total returns not only beat inflation, but more than doubled in value (Figure 6). They have thus outperformed investments in the UK and USA. Commercial real estate investments in the UK have hardly protected their value against inflation. The NAREIT Index for the USA developed similarly. (We also want to remind you that the cumulative total return indices assume that distributions are always reinvested in real estate.)

The result from the UK means that real estate can offer protection against inflation even in a “greater” stagflation. Since Switzerland did not really experience stagflation in the 1970s, we cannot apply this term to Switzerland either.

Unfortunately, it must also be said that in the 1990s Switzerland gave up the lead (in returns) it had gained over the USA and the UK in the 1970s. The problem was the pronounced real estate bubble at the end of the 1980s, which caused depreciation in Switzerland in the 1990s to be similar to that in the USA during the subprime crisis. Both the nominal price indices and the real total returns illustrate the prolonged bear market in Switzerland during the 1990s.

Figure 5: Nominal price indices

Source: Mihnea Constantinescu, Peter Scott, CUREM, Bloomberg, FRED, Macro Real Estate

Figure 6: Real total returns

Source: Mihnea Constantinescu, Peter Scott, CUREM, Bloomberg, FRED, Macro Real Estate

Key take aways

The topic is complex, but let me summarize it briefly:

- The first oil price crisis led to a marked decline of values of investment properties in the UK, the USA and Switzerland, both nominally and in real terms

- UK commercial real estate went trough a deep crisis in 1974-1975. In contrast, the Swiss real estate indices were soon pointing upwards. Swiss real estate (above all residential investment properties) provided successful protection against inflation and created additional value for investors

- But even in the UK, which was struggling with overwhelming inflation problems, capital values recovered. However, in real terms, total returns fell for three consecutive years (1974-1976) before staging a recovery.

- The rise in interest rates was also significant in Switzerland in the early 1970s (approx. 200 basis points between 1972 and 1974). Inflation remained above 10% for some quarters. The brutal appreciation of the CHF as one of the consequences of the abandonment of “Bretton Woods” led to substantially lower interest rates again. Mortgage interest rates in Switzerland reached in the second half of the 70ies much lower levels the pre-oil-crisis. But this came at a price: the appreciation of the CHF has led to a number of economic problems that should not be underestimated

- Compared with other countries, where stagflation prevailed, the trend towards lower mortgage interest rates in Switzerland was an aberration. Mortgage rates in the US and UK only fell in the 1980s, when Volcker, for example, took tough measures to get inflation under control

- If Switzerland wanted to decouple itself from other countries in the event of a possible stagflation, the CHF would have to appreciate again significantly. Or we would need to see a complete loss of confidence and a structural weakness in the USD or EUR. So we dont have high hopes of a decoupling of Swiss macroeconomic development from other countries in the current environment. Switzerland would therefore go trough a stagflation, even if a slight strength in the Swiss franc would somewhat reduce the effects in Switzerland.

- If we look back at the years 1970-1990, we also have to realize that the good protection against inflation was also due to the fact that real estate was able to deliver robust income returns at the time

- Unfortunately, the higher interest and yield levels at that time suggest that – before inflation protection takes effect during an inflationary phase – the currently extremely low net yields need to rise. (This applies not only to Switzerland but also to some core markets abroad)

- Such a trend towards substantially higher net yields could, on the one hand, be painful for investors who are caught flat-footed. On the other hand, the experiences from this higher phase of inflation also give hope that real estate really does offer protection against inflation after an initial shock. One should therefore already prepare mentally and financially for such enormous opportunities.

Uncertainties remain high at the moment and the situation needs to be monitored closely. Nobody knows today whether we will see a stagflation or just a slowdown. Neither do we economists who make forecasts. The situation is very path dependent.

Macro Real Estate is staying up to speep with the evolution in real estate investment markets both in Switzerland and international. Don’t hesitate to contact me directly should you have any questions.

Zoltan Szelyes

Leave A Comment